The FIRE Decision Tree: Buy vs Rent vs Relocate (A No-Drama Framework)

Housing advice online is usually dogma disguised as math:

- “Equity.”

- “Invest the difference.”

- “Geoarbitrage.”

If you are pursuing FIRE and you have a housing decision within 12 months, you do not need a team to join. You need a framework.

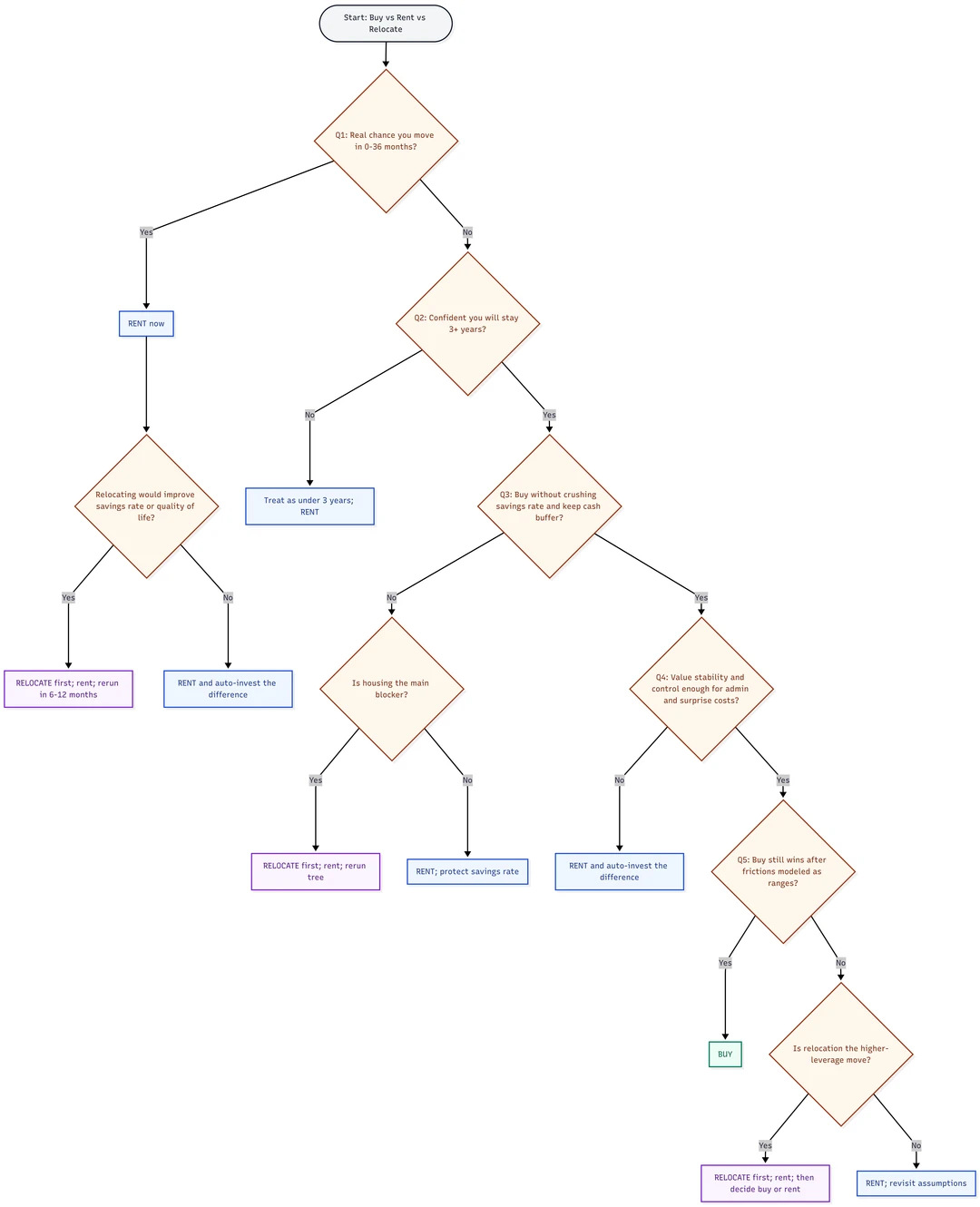

This post gives you a values + math decision tree that ends in one of three outcomes:

- Buy

- Rent

- Relocate (and then buy or rent)

The trick: most outcomes are dominated by a few swing variables, not ideology.

Why this is a FIRE problem, not a culture war

Housing is structurally important because it is structurally large.

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics notes that shelter is one of the largest parts of the CPI market basket. In the CPI relative importance data for December 2025, shelter is 35.625% of the market basket. Rent of primary residence is 7.840%, and owners’ equivalent rent is 26.204%.

Translation for FIRE: if shelter is your biggest recurring expense, small monthly differences compound into big timeline differences.

So the right housing choice is the one that best supports:

- your long-run savings rate

- your flexibility (optionality)

- your ability to stick with the plan without burning out

TL;DR: Run the tree in 5 minutes

The 5-minute decision tree (scan this first)

Use your pessimistic answers (your downside), not your optimistic ones.

- Q1: Is there a real chance you will move in the next 0-36 months?

- YES -> Default: RENT now.

- Then ask: would relocating significantly improve savings rate or quality of life?

- YES -> RELOCATE (rent first), then re-run this tree after 6-12 months.

- NO -> RENT and invest the difference automatically.

- Then ask: would relocating significantly improve savings rate or quality of life?

- NO -> Go to Q2.

- YES -> Default: RENT now.

- Q2: Can you confidently say you will stay 3+ years?

- NO -> Treat as under 3 years -> Default: RENT.

- YES -> Go to Q3.

- Q3: Can you buy without crushing your savings rate AND still keep a cash buffer?

- NO -> Default: RENT (or RELOCATE if housing is the blocker).

- YES -> Go to Q4.

- Q4: Do you value stability/control enough to accept ownership admin and surprise costs?

- NO -> RENT (and invest the difference).

- YES -> Go to Q5.

- Q5: Does the buy math still win after you model realistic frictions?

- Model: rate, closing costs, ongoing maintenance, and exit costs as a range.

- If BUY wins in the pessimistic case -> BUY.

- If it only wins in the optimistic case -> RENT (or RELOCATE).

Default rules by tenure bucket

- Under 3 years: renting usually wins because entry and exit costs dominate.

- 3-7 years: it depends heavily on rate and transaction frictions, model ranges.

- 7+ years: buying becomes more competitive if you can keep your savings rate high.

Model these 3 numbers first

- Your expected time horizon (and a pessimistic time horizon)

- Your financing cost (your mortgage rate)

- Your transaction frictions (upfront + exit) as a low/medium/high range

Now, details and the “why” behind each branch.

The decision tree, step 1: values and constraints (no math yet)

Start with constraints. If you skip this, you will do a perfect spreadsheet for the wrong life.

Mobility requirement

Ask this plainly:

- Is there a real chance you will change jobs, cities, or household structure soon?

- Would you take a better role if it required moving?

- Are you unsure about school districts, caregiving, or relationship plans?

If your honest answer is “yes, probably,” that is not indecision. That is information.

In the tree, mobility pushes you toward renting now.

Stability requirement

Stability can be practical:

- a child needs continuity

- caregiving anchors you

- health makes moving costly

- you run something from home that benefits from control

If stability is a real need, buying can be FIRE-aligned even if the spreadsheet says renting is slightly cheaper. The framework is not “maximize a number.” It is “maximize your ability to keep saving.”

Risk and admin tolerance

Owning is not just a payment. It is exposure to:

- maintenance uncertainty

- insurance changes

- local taxes and rules

- time spent managing repairs

Renting is exposure to:

- lease terms and landlord decisions

- rent increases over time

- less control over the space

Map this directly to branches:

- Risk-sensitive + admin-sensitive tends to favor renting.

- Stability-sensitive tends to favor buying (if tenure is long enough).

The decision tree, step 2: tenure buckets (the branch most people skip)

Tenure is the quiet kingmaker because transaction costs are real and front-loaded.

The National Association of Realtors reports that the typical 2024 seller lived in the home for 10 years. That is long enough for many costs to amortize. But FIRE pursuers facing a move within a few years are in a different math regime.

Use three tenure buckets:

- Under 3 years: short

- 3-7 years: medium

- 7+ years: long

Here is the anti-rationalization rule:

- If you cannot confidently say 3+ years, treat it as under 3 years for decision purposes.

Why this matters:

- short tenures magnify entry and exit costs

- short tenures increase the odds of selling at a bad time

- short tenures are where “but equity” arguments usually break

FIRE-friendly mindset: plan around your downside.

The decision tree, step 3: the three swing variables in the math

Once values and tenure are clear, run the math with three high-impact variables.

Swing variable 1: financing cost (your mortgage rate)

Financing cost changes everything because it sets your cost of capital for buying.

Freddie Mac’s weekly Primary Mortgage Market Survey reported the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage averaged 6.01% as of February 19, 2026. At rates like this, interest expense is a bigger headwind in the early years, and breakeven tenure often moves further out.

Practical implication:

- higher rates do not automatically mean “do not buy”

- higher rates do mean “be stricter about tenure and savings-rate impact”

Swing variable 2: transaction frictions (costs to enter and exit)

For FIRE, transaction costs are not a footnote. They are a timeline event.

On the way in:

- Bankrate reports buyer closing costs vary by state and can range from under 1% to nearly 3% of the purchase price (methodology and inclusions vary).

On the way out:

- Sale transaction costs can be several percent of the sale price and vary by market and representation choices.

- Federal Reserve research discusses how broker compensation has historically worked, and why the structure can matter for costs.

Do not anchor a single percentage. Model a range:

- Exit cost low / medium / high

Then see whether buying still wins in your pessimistic scenario.

If you are under 3 years, this is the whole ballgame: a few percent of a home price can equal multiple years of “monthly savings” you thought buying would create.

Swing variable 3: invest-the-difference assumptions (behavior is part of the math)

The internet loves “invest the difference.” In real life, many people do not.

Your tree needs a behavior reality check:

- If you rent, will you actually invest the down payment and any monthly savings?

- If you buy, will you actually keep your savings rate high after the purchase?

Use a conservative assumption based on your history:

- If you have a track record: assume you invest 70% of the difference.

- If you are unsure: assume 30%.

- If you know you will lifestyle creep: assume 0%.

This is not a moral judgment. It is forecasting.

Buy, rent, or relocate: how to pick the winning branch

Think in “mostly true” conditions. You do not need perfection across every line item.

When buying tends to win for FIRE

Buying is often FIRE-aligned if most of these are true:

- Tenure is long (7+ years), or medium with strong confidence

- You can buy without crushing your savings rate

- You still have a cash buffer after closing

- You are comfortable with maintenance uncertainty and admin

- You model realistic frictions and buying still wins in the pessimistic case

Simple sanity check:

- If buying drops your savings rate so hard that you stop investing, the “equity” story is not saving you.

- If buying increases stability so much that you earn more, save more, and avoid disruptive moves, it can be worth it even if it is not the cheapest monthly option.

When renting tends to win for FIRE

Renting is often FIRE-aligned if most of these are true:

- Tenure is short (under 3 years) or uncertain

- Buy costs are high relative to rent for an equivalent lifestyle

- Rates make early-year interest a heavy headwind for you

- You value flexibility

- You will invest the difference automatically

Two blunt truths:

- If you rent and do not invest the difference, you are not “winning the rent math.”

- If you rent and automate investing, renting can be extremely rational, especially in short or uncertain tenure windows.

When relocating is the highest-leverage move

Relocation is the branch people avoid because it is socially loaded. But in FIRE math, it can change both sides:

- income

- cost of living

Relocating is often FIRE-aligned when:

- housing costs are the main reason your savings rate is stuck

- your work is portable, or you can credibly switch markets

- you have a plan for community and support systems (so the move is sustainable)

Example scenario (not a promise, just a way to think):

- If a move drops housing costs by 25% without reducing income, you may create a major savings-rate upgrade.

- If income rises and costs stay similar, that also upgrades savings rate.

- If income drops but costs drop more, it can still win.

Key FIRE rule:

- Do not relocate only for lower costs if it isolates you or increases burnout risk.

- Do relocate if it improves your life while improving your savings rate.

Myth-busting: the homeowner wealth gap and what it does and does not prove

You will hear some version of:

- “Homeowners are way wealthier than renters, so buying is always the FIRE move.”

The wealth gap is real, but it is not a proof-of-causation sticker for your situation.

Three reasons this stat can mislead:

- Selection effects: higher-income households are more likely to buy.

- Lifecycle effects: older households are more likely to own and have had more time to accumulate assets.

- Forced savings and leverage: mortgages can force equity buildup and add leverage, which can grow wealth, but also adds risk.

The FIRE takeaway:

- Buying can be a wealth-building path under the right assumptions.

- Buying is not automatically optimal for every tenure, rate environment, and lifestyle constraint.

- A framework beats slogans.

A one-page checklist you can run this weekend

Step 0: Write your decision in one sentence

- “I am choosing to buy because…”

- “I am choosing to rent because…”

- “I am choosing to relocate because…”

If you cannot finish the sentence without defending yourself to the internet, you are not done with Step 1 (values).

Step 1: Gather inputs (15 minutes)

- Your realistic tenure estimate and pessimistic tenure estimate

- Your rent for an equivalent lifestyle

- A realistic mortgage rate you can actually get

- Estimated buyer closing costs

- A low/medium/high estimate for exit costs

- A maintenance buffer assumption

- Your invest-the-difference behavior assumption (70/30/0 based on history)

Step 2: Apply default rules (2 minutes)

- If tenure is uncertain: treat as under 3 years.

- Under 3 years: default rent.

- 3-7 years: only buy if pessimistic case still works.

- 7+ years: buying becomes more competitive, but savings rate still rules.

Step 3: Run three scenarios (10 minutes)

- Optimistic: best reasonable inputs

- Realistic: most likely inputs

- Pessimistic: downside inputs

Decision rule:

- Choose the option that works in the pessimistic case and feels sustainable in real life.

Step 4: Quick sanity checks (3 minutes)

- Will this choice increase or decrease my savings rate over the next 12 months?

- Does this choice increase or decrease my flexibility?

- Am I modeling transaction frictions as ranges, not a single number?

- Am I assuming behaviors I do not have a track record of doing?

Step 5: Common failure modes to avoid

- “We might move, but let’s buy anyway.” -> treat as under 3 years.

- “Renting is cheaper, but I won’t invest the difference.” -> renting loses its FIRE advantage.

- “Buying is building equity, so it must be good.” -> equity can be expensive if it crushes savings rate.

- “Relocating is scary, so it is not an option.” -> at least price the option.

Step 6: What to do after you decide

If you choose BUY:

- commit to a post-close savings rate target

- keep a maintenance buffer

- set a minimum stay rule before selling (unless life forces it)

If you choose RENT:

- automate investing the difference on payday

- set a rent increase buffer in your budget

- calendar a re-run of the tree in 6-12 months

If you choose RELOCATE:

- budget the one-time move cost honestly

- plan your support systems

- rent first if you are not sure about the neighborhood, commute, or culture fit

Sources

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS): CPI factsheet on owners’ equivalent rent and rent, including December 2025 relative importance data (shelter, rent of primary residence, owners’ equivalent rent).

- National Association of Realtors (NAR): Quick Real Estate Statistics, including typical 2024 seller tenure (10 years).

- Freddie Mac: Primary Mortgage Market Survey (PMMS), including the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage average as of February 19, 2026 (6.01%).

- Bankrate: Average closing costs by state (2025), reporting state variation and ranges commonly under ~1% to nearly ~3% depending on methodology.

- Federal Reserve (FEDS Notes): Research note on real estate broker compensation and why commissions and transaction costs matter, emphasizing variation and structure.